Innovation has been part of Madeira Wine’s DNA since its beginnings, as has its export vocation.

Vitis vinifera is not part of Madeira's native flora. The first grapevines were probably planted by the Portuguese, after its discovery around 1419. Alvise Cadamosto, a Venetian explorer, visited the island in 1455 and reported on the cultivation of Malvasia [Cândida]. This famous grape variety, that played a pivotal role in Madeira wine production, was used to make the wine that became known in England as Malmsey. It was highly appreciated in the markets of northern Europe since the 15th century, and its introduction was probably motivated by the possibility of exporting to this same market. According to Alvise Cadamosto, it was Prince Henry himself who ordered the first grapevines from Cândia, a kingdom in Crete, then under the rule of the Most Serene Republic. However, it was not the only variety to be acclimatized early, since Cadamosto's account also mentions vines laden with red grapes. Later, around 1530, his fellow countryman Giulio Landi testified to the existence of “white varieties other than Malvasia”. With these, the islanders made a wine, which this author compares to “Greco di Roma”.

Wine gradually became the islanders’ main currency. From then on it was increasingly shipped to overseas territories, particularly Brazil. In 1580, Gaspar Frutuoso described in detail the island’s vineyards along the entire coastline. In addition to Malvasia, he repeatedly alludes to what he calls “vidonho”, although it is not known for sure whether he refers to a specific grape variety or to a group of several different vines. In 1689, John Ovington mentions Malvasia and “tento”, which may correspond to the red grape, which Cadamosto had already mentioned in the mid-14th century. Like Hans Sloane two years earlier, he mentions the curious habit of exposing the casks to the sun during the fermentation phase and adding plaster to the must.

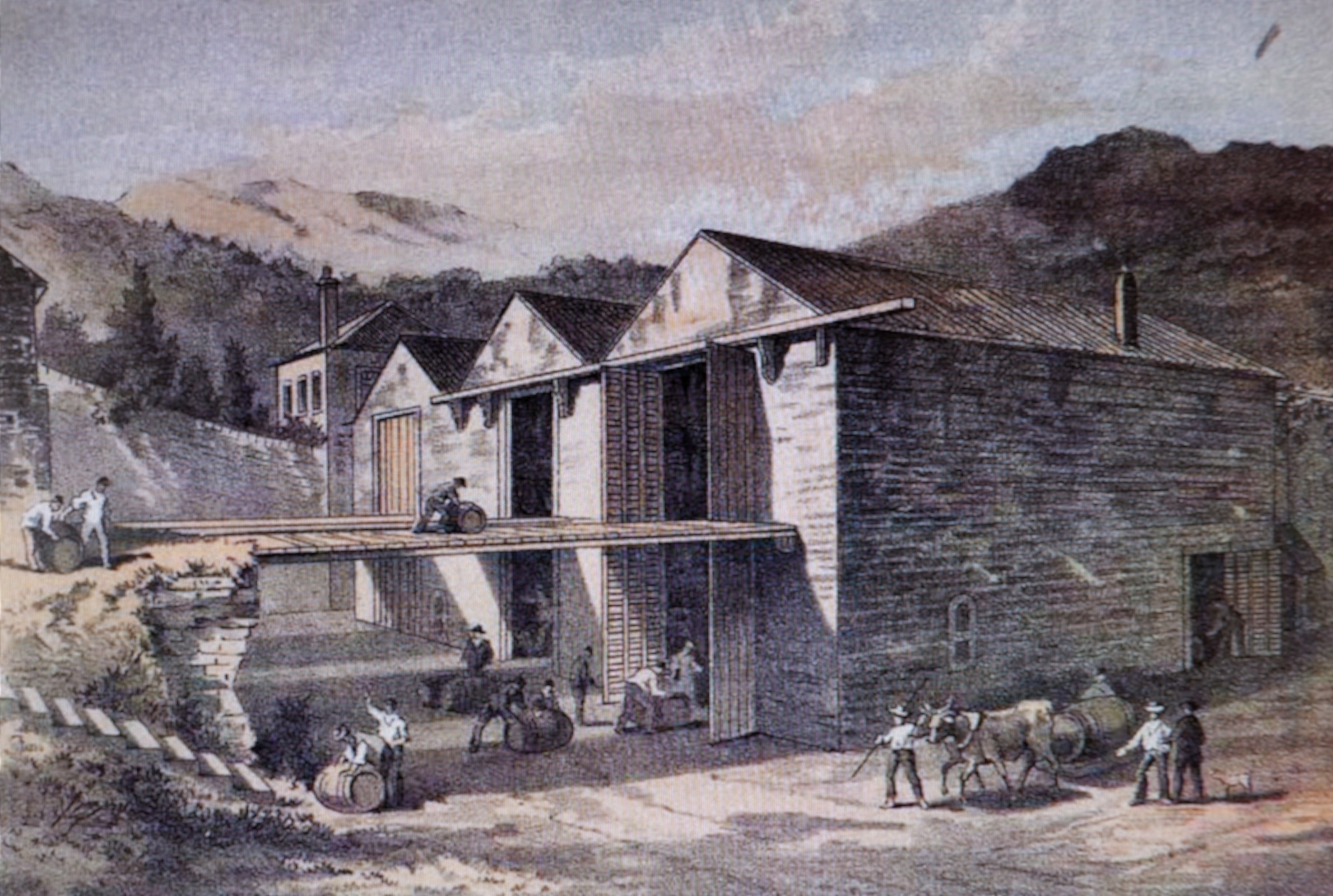

By the second half of the 17th century, two thirds of the wine produced on the island was already being exported. It is known that the colonies on the American continent and in the West Indies maintained a privileged commercial relationship with Funchal after the restoration of Portugal's independence in 1640. At the end of that century, the main destinations for barrels from Madeira were New England and the West Indies. From the beginning, the port of Funchal attracted businessmen of various nationalities. Among them were the English, who benefited from a very favourable situation and prospered in the following centuries as wine exporters.

In the first half of the 18th century, Madeira wine was not very popular among Londoners, who could buy it at a lower price than an ordinary white wine. In the following decades, the production process evolved, as a result of innovations that substantially altered its organoleptic characteristics, similar to what happened to its Atlantic competitors at the same time. The practice of adding brandy to the must was first tried in the Bordeaux region. Around 1750, island producers adopted this technique. They began using French brandy, which was replaced a few decades later by locally produced brandy, allowing them to make the most of lower quality grapes. Some of the exported wine was now aged for a few years before being shipped.

It was around this time that Madeira Wine began to gain fame as a cosmopolitan and refined drink, which contributed to an exponential increase in demand for it, as well as its value in import markets. It was also at this time that it began to be used in cooking, first in the British Atlantic and only later in France, as a premium ingredient.

Several authors argue that its sudden popularity in the United Kingdom was due to the return of veterans from the American War of Independence and the increase in triangular trade - the exchange of goods between England, America and the Iberian nations. However, if we are to believe what John Croft writes, it was already in great demand in London in the 1750s, due to its medicinal properties.

Its price now reached very high values in that market, especially if it was "vinho de roda", naturally obtained during a round-trip transatlantic voyage through the tropics.

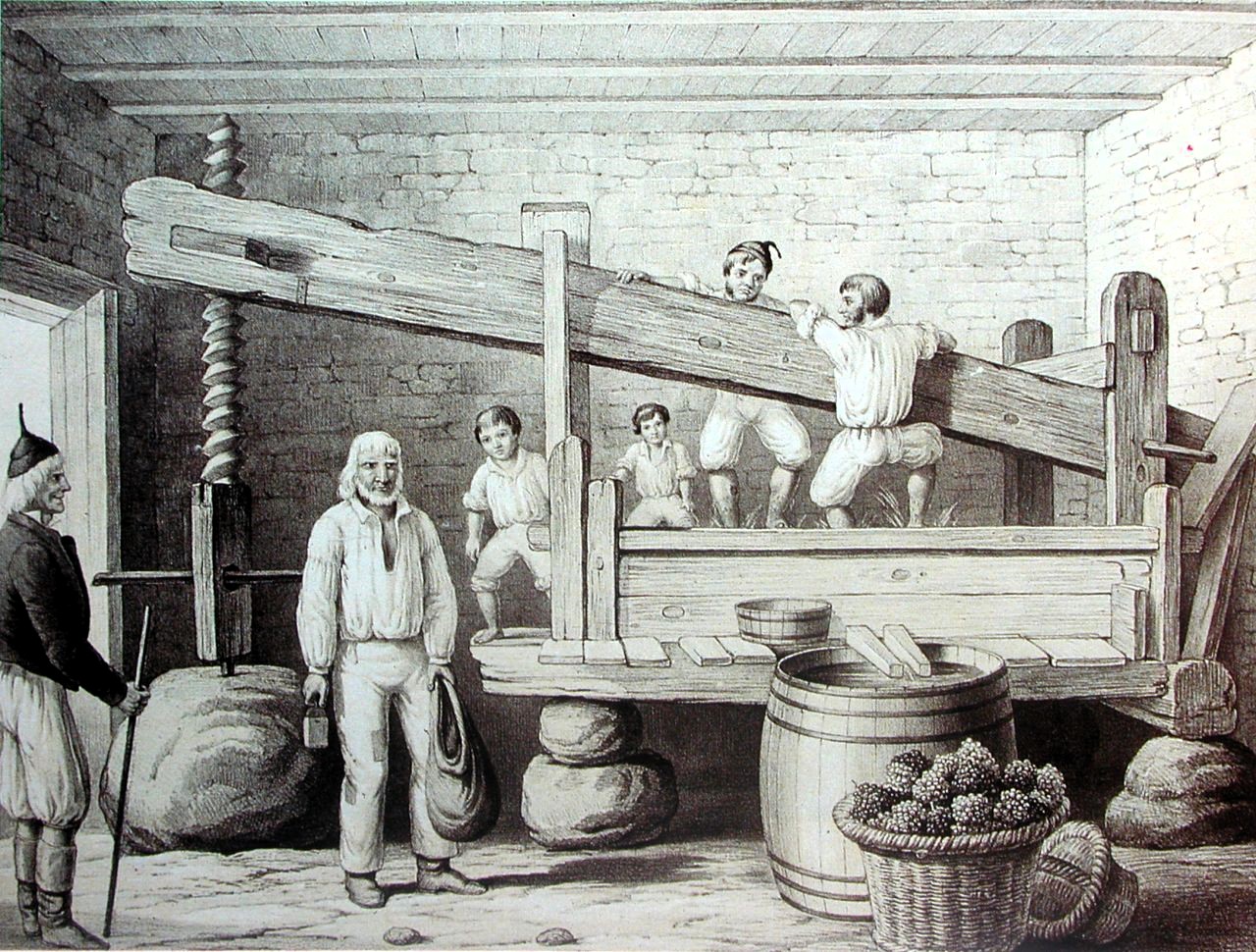

To meet the increased demand, exporters ended up inventing a revolutionary technique at the turn of the 1800s. It was now possible to accelerate the ageing of wine before shipping, by artificially heating it in “estufas” for a few months.

Source: Cossart, Gordon & Co |Established 1745 | the Oldest and by far the Largest Shippers of Madeira Wines – Export marketing

The categories of Madeira Wine were, at that time, very different from those enshrined in current legislation, which leads us to relativize the belief that it was “invented” between the end of the 17th century and the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Sources from this period generally distinguish between dry wine, a dry wine obtained from a mixture of only white or white and red grape varieties, and sweet wine, a very sweet white wine with a naturally high alcohol content. Malmsey, made only with Malvasia Cândida must, produced by the islanders since the time of Cadamosto, was still in great demand. As for dry wine, in 1760, there were already three classes for sale on the London market: common Madeira, London market and London particular, the latter being the most prestigious. It would be produced with grapes harvested from the best vineyards on the south coast of the Verdelho and Boal varieties and, perhaps, some Vidonho.

The golden age of Madeira wine was about to begin, lasting for several decades until the end of the Napoleonic invasions. Regional historiography portrays what followed as an almost continuous sequence of setbacks, due to causes that cannot be discussed here. Much emphasis has been placed on the devastating effects of powdery mildew, which spread to the island's vineyards in 1852, followed by the phylloxera plague in 1872 and downy mildew in 1912. On the other hand, the innovations introduced into the production process during this downward trajectory have received little attention from researchers.

Export routes have also changed, with Northern Europe now the main market. The armed conflicts that have ravaged the world since then and certain political events in importing countries, such as Prohibition in the United States, or global events, such as the 1929 financial crisis, are said to have brought an end to the wine cycle in Madeira. From then on, the island's economy would become increasingly dependent on tourism. After a long journey through the desert, producers were able to respond to this new situation, mainly due to their resilience. By modernising infrastructure, equipment, and production techniques, and by strengthening the technical and scientific monitoring of their activity, they were able to once again adapt the ancestral know-how that they inherited from their ancestors to the new demands of the markets.